Creativity walks a tightrope. If you are not creative enough, your readers will be bored. If you are too creative, your readers will be mystified.

“Oh!” says the Creative Soul. “That’s what I want. I want my reader to be mystified.”

Not this way, you don’t. I mean mystified as in “mixed up, baffled, confounded, deceived and perplexed.” None of these are particularly happy emotions, especially “deceived.”

Yes, there is a challenge in reading a piece of work that sets a puzzle you must solve in order to understand it. For many experienced readers, the joy of solving the puzzle is a great part of the pleasure of reading. Witness the popularity of Joyce’s “Ulysses.”

But…

This joy comes from communication with a kindred mind. We picture you, the author, setting this puzzle, crafting it with skill, leading us in, leading us on, creating “a riddle wrapped in an enigma, inside a mystery.” We accept the challenge and dive into the unequal competition. “Unequal,” of course, because you, the writer, are setting the rules and doling them out to us in your own sweet time. We expect you to play fair with us and at least stick to the rules of your game.

It’s all sorts of fun to be the author, isn’t it? The power of control? Being completely in charge of the whole game? But beware. The reader has one power you can never challenge: the ability to close the book, put it down and never pick it up again.

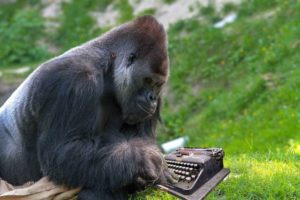

Monkeys on Typewriters

When creativity approaches a certain stage of randomness, communication fades, and readers are very sensitive to anyone wasting their time. So you must never, ever, give us the impression that you are cheating. Obscurity for the sake of obscurity gets old really fast. In order to keep us reading, you must always keep us believing that there is a meaning and a purpose to the weird and wonderful events in your story.

And before you answer, “But that’s the theme of my story. That there is no meaning or purpose to life. So I put the reader through the experience to demonstrate…” and yadda, yadda, yadda. Sure. And as every theatre director knows, if you portray boredom by boring your audience, you soon have no audience.

The Most Important Rules of All: Grammar

So mystify the reader with clever plot twists and double entendres, not by breaking the rules, especially those rules generally accepted as basic to communication: the rules of grammar. For example, a simple sentence from a novel I was reviewing which had a very creative and original style:

“The Shadow World was born of this magic. It taps into this magic to keep it alive.”

Yes, dear Writer. We know you want to be all mystical and mysterious, but we don’t know what is being kept alive: the magic or the Shadow World itself. Which did the author mean? Perhaps both? Is the double meaning intentional? Is it meant to intrigue us to get us to read on to find out? Or, heaven forbid, is this just an example of pronoun misuse? The echo of “this magic” confirms our suspicions. This author is just not very good at using pronouns.

Creative sentences can become awkward, and the writer, in love with his own creation, doesn’t always recognize when the boundary is crossed. That’s fine. We can disregard one or two errors of that sort. If you have paid your dues and persuaded us that you know your chops, we can parse the sentence and realize that you would have used “itself” instead of the last “it” if you had meant the Shadow World.

But if the book is full of misused words, misplaced commas and other errors, we do not get the pleasure of puzzling over what should be a pleasant conundrum. We just shrug our shoulders and say, “Another writing error,” and move on, disappointed. If we are disappointed too often, we close the book.

I know you think you’re being artistic and creative and disregarding convention so you don’t have to be so careful about all those old things they taught you in school. Sorry, but readers are suspicious you are being lazy and self-indulgent and you are misusing the tools of your trade that exist to aid the communication of your ideas to the world. Then we become suspicious. If your communication skills are that poor, will your ideas be worth digging for?

A poet chooses words carefully, taking the same time to write a line that a novelist takes to write a chapter. As an artistic novelist, you tread a tightrope between the two media, and you must take your hints from both.

Remember Your Reader

If you are writing creative and innovative literature, think about your possible readership. They will probably be educated, experienced readers. These people know when they see grammar and spelling errors.

Know the rules and follow them so that breaking them becomes meaningful. You’ll beat the monkeys on typewriters every time.

So true, Gordon. Creative style can be a good thing – only until it’s so far from the norm that I have to work too hard to read it.

Totally agree, Gordon. As I’ve said before, I don’t want my readers to even see my words; I want them to look through them to the movie in their mind. If they keep getting stuck on weird words or have to stop to try to figure out what I’m trying to say, the movie lurches to a halt. I want my readers to immerse themselves into the flow of the story. A smooth ride is the way to go.

I like what you wrote, Melissa. This rings true for me, in my experience as a reader. From the time I was a child, I have read many books, because I love stories. Good writing fuels the imagination, as the reader becomes immersed in the narrative. I don’t want it to feel as if I’m reading a textbook, although if it’s well written and the subject is interesting, even reading a textbook can, in some cases, become enjoyable.

Thanks, Mary Kay. Glad we’re on the same page!

Just now had a book submitted to me for review with no quotation marks and no changes of paragraph for changes of speaker. It made it difficult to read, and I couldn’t see any way it added to the experience.

I offered the guy editing help. 🙂

Hi, everybody:

I think I’ve just about reached my limit of authorial clever-dickery.

For the last two weeks I’ve been slogging through The English German Girl (Jake Wallis Simons).

Speech is introduced by em-rules. It took a while to get used to it.

I like my paragraphs to be two or three sentences. Mr Simons writes paragraphs that can go for a page or more. You have to concentrate.

I have persevered because at the guts of it is a great story – a Jewish girl sent by her family in Berlin to live with relatives in England.

But I’m not going to bother with Forbidden Love in St Petersburg (Mishka Ben-David). No quote-marks at all. Already I can’t be bothered with it and so it will go back to the library today or tomorrow.

Cheers

– Paul Corrigan

I have to admit I managed to get through “One Hundred Years of Solitude,” which has no very little paragraphing and no quotes, as I remember, and I rather enjoyed it. It’s amazing what you can get used to.

I think the point is that the geniuses can do things like that because they do it for a reason. Different for the sake of being different usually creates crap.

Very interesting

Style should augment, not intrude.

That’s it, in a nutshell.