Okay, everyone knows that great works of literature have important themes. “Red Badge of Courage,” “Les Miserables,” “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.” You know the ones. But what about your Space Opera?

Okay, everyone knows that great works of literature have important themes. “Red Badge of Courage,” “Les Miserables,” “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.” You know the ones. But what about your Space Opera?

Why Bother?

“It’s just fiction,” you protest. “It’s entertainment. People don’t want to be preached at. Why should I bother my readers with a theme?” Well, you’ve got the preaching part right, but no matter how focused on entertainment a story may be…

There Must Be a Theme!

To paraphrase my old friend Thumper the Rabbit,” “If you ain’t got nothin’ to say, don’t say nothin’ at all.”

The lowly Western has done more damage to the collective American psyche than any other form of entertainment due to its recurring themes of racism, anti-cooperative independence, resistance to governmental authority and rigid adherence to outmoded codes of violence. But plenty of people enjoy Western books and movies. People, even the least intelligent and poorest educated, want ideas in their entertainment.

If you aren’t reaching out to readers with an idea that they can apply to their own lives, they won’t become immersed in your work. People buy books for two associated reasons: because the book entertains them and because the book reaches out to them. The successful book does both. In general, fiction tends to lean towards the entertainment side and nonfiction does more reaching out, but no matter what you are writing, you have to connect to people with ideas.

Okay, So What is Theme?

Be careful when you start a theme statement with “This is a story about…” because if your next words are “…someone who…” then you’re probably talking about conflict or character. If your next words are one of the items listed below, you’re not stating a theme at all.

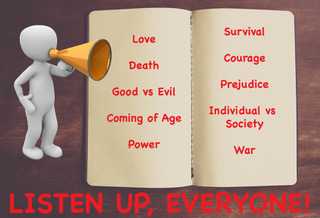

The Usual List of Popular Themes:

- Love

- Death

- Good vs Evil

- Coming of Age

- Power

- Survival

- Courage

- Prejudice

- Individual vs Society

- War

- And yadda, yadda, yadda.

Sorry, this is NOT a list of themes. Love is a genre. Good versus Evil is a conflict. War is a setting. Courage and prejudice are character qualities, and the rest are discussion topics. Your specific theme will be your personal take on the topic you are discussing: “War is fun,” “Most people don’t understand courage,” or “Even you can impress your in-laws (if you use this recipe for Baked Turkey Pie).”

Show Your Theme; Don’t Tell It

A piece of common wisdom says to state your theme a minimum of three times during the story, with changing emphasis as the story arc progresses. My added wisdom is that three times should be the maximum number as well, because stating the theme is “Telling.” All of the rest has to be “Showing.” The most dangerous advice for a writer to follow is “Tell a Story.” A good writer demonstrates the truth of a theme by showing characters performing actions that bear upon that theme.

Don’t Be Too Obvious

The “showing, not telling” part of writing also means involving the reader in the decision-making process. Don’t try to control readers; they don’t like it. Don’t tell them the theme over and over again. If they disagree, nagging won’t change their minds. Demonstrate the idea in action, and let them draw their own conclusions. All else is preaching. But when you’re writing all that wonderful action, keep firmly in your mind that it’s supposed to mean something. If it doesn’t, then you’re writing a Transformer movie script. And even those have themes.

Starting With a Theme is Dangerous

It’s probably a bad idea to start out with, “I’m going to write a book showing how power corrupts.” If you have “power corrupts” firmly held in your mind’s eye as you write, you’ll probably keep saying it over and over. Which is fine for a Sunday sermon; not so good for a novel. Some of my most thoughtful books started out with a character in a situation. It was only after I had been writing for a while that I realized why that character appealed to me so much. It was because he or she embodied something I believed in. That became my theme, and I could use it to help decide which actions and characters to add at later stages of writing.

What’s Your Point?

Because that’s the point of writing. To show people examples from life to demonstrate how they should live. Or not live, as the case may be. Not that you’re going to change the world. Your most loyal readers like your books because your themes affirm what they already believe. As, unfortunately, the Western and other pulp fiction tends to do. But if you strike the right balance between what people believe and a truth that might move them in a new direction, you can write a popular book that affects how people act.

But when you’re tempted to slip in just a little more of that sermon, because people really need to change, remember: If they don’t like the book enough to read it, what good can it do them? And if you’re tempted to leave a theme out completely, consider the fact that nobody will remember your meaningless book, even if they manage to finish it.

Excellent advice, although, as a writer in the western genre who is trying to show a truer picture of the Old West than has been the practice in the past, I kind of resent the term ‘lowly western.’ The western is a uniquely American genre–albeit now popular in Europe and other parts of the world, about a particular period in US history. That writers, filmmakers, and sometimes even historians tended to distort that history by demonizing Native Americans, ignoring women, and leaving out ethnic minorities is lamentable, but nowadays the western is undergoing a resurgence and the new breed of writers, many at least, are trying to paint a more accurate picture. As for theme, you are absolutely correct; and even the ‘lowly’ westerns of the past, for all their faults, had underlying themes that were illustrated by the characters’ actions.

Charles, apologies for anyone in your situation, trying to make a silk hat out of a ten-gallon Stetson 🙂

I’ve always been a Western fan, and I use them as an example because I know them well.

Well stated, Gordon. If there’s no “point” then “what’s the point”? It need not be super deep or heavy, but it does need a reason to be written.

Sermon alert! “The lowly Western has done more damage to the collective American psyche than any other form of entertainment…” LOL

For me, the theme doesn’t develop until after the story has. In my newly self-published debut novel, I had an idea and then started writing. I treat the characters almost like real people – it takes a while to get to know them. Some are more open than others; some are more likeable than others. Regardless, I let them tell me their story or how they view the situation at hand, which has become the subject of the tale – the one that piqued my interest and caught my attention in the first place. After just about everything came out and all was said and done, I realized what the theme was: you never really stop loving someone. This latter statement is a line spoken by one of the characters. But I didn’t intend for it to sound so dramatic or uplifting. It’s just something she said to the protagonist and thus, it became the theme.

Writing fictional stories isn’t like writing operating procedures manuals, which is what I do in my technical writing. With SOPs, there’s a specific goal in mind from the outset: a certain procedure or set of procedures has to be explained and/or described. There’s particular verbiage congruent with the industry one has to use to make things clear. Fiction writing isn’t always so clear-cut. It’s more emotional and subjective. But, of course, that still depends on what the writer is trying to do with the story.

Alejandro, as I mentioned, I usually don’t start with a theme, either. It develops from the story at some time as I’m telling it. However, if I finish the whole first draft and still haven’t discovered the theme, when I go back over the story I find it wandering and unfocused. I wrote this article because I often review novels that never did get it together to say anything specific. Worse still, sometimes events seem to contradict ideas that the author has set up. At some time before writers present their work to the public, they need to know what they are saying.

Gordon, enjoyed your article, thank you.

What did you really mean by that, Allen? (LOL)

Thanks. Glad you enjoyed it.

You’ve just given me a lot of insight. Thank you.

Thanks, Gail. Insight sounds rather profound, despite my quoting of a Walt Disney character 🙂