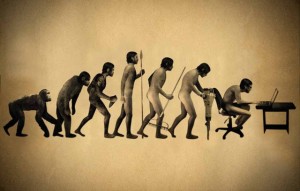

In Melissa Bowersock’s article, Conflict: The Heart of Storytelling, she wrote, “Storytelling is as old as human DNA. As old as language. As old as Joe Neanderthal sitting around the fire at the mouth of his cave, telling the group what happened that day. ‘Me went hunting, threw rock at rabbit, killed it, brought it back. Good day. Ug.'”

In Melissa Bowersock’s article, Conflict: The Heart of Storytelling, she wrote, “Storytelling is as old as human DNA. As old as language. As old as Joe Neanderthal sitting around the fire at the mouth of his cave, telling the group what happened that day. ‘Me went hunting, threw rock at rabbit, killed it, brought it back. Good day. Ug.'”

As old as language. There are many theories about how language developed. As recently as April 2015, researchers at MIT said language developed rapidly. Human speech wasn’t a series of mumbles and grunts. Rather, humans combined two kinds of communication, one from birds and the other from monkeys.

But my unscientific theory is that language developed because humans have a deep-seated need to tell and hear stories. Our thinking is on a higher order. We have curiosity that is light years beyond the kind that “killed the cat.” Possibly the most important part of our intellect is the ability and desire to ask why, to want to know the answers. To put it in modern terms, the cat wants to know what is inside the box. The human wants to know why the cat can be alive in one reality and dead in another when an observer opens the box (see Cat, Schrödinger’s).

We have imagination. We daydream. We concoct stories in our minds. We envision possible outcomes. We wonder, ruminate, and ponder. And, we need to communicate our thoughts to others. Of course, as hunter/gatherers, we needed to communicate vital survival information (e.g., which Wildebeest to single out, where to dig for the best yams, if a lion was nearby, and so forth.) This is the kind of thinking seen in predators (hunt the Wildebeest) and prey (the best yams, where’s the lion?). Our human brains, however, go beyond simple survival mode into abstract thinking. We want to understand what we experience (what is the cause and effect?)

If we can’t understand something, we’ll make up a tale which seems plausible. Thus, a story is born. An example would be when a primitive tribe explains the terrifying phenomena of thunder and lightning by the “obvious” existence of an anthropomorphized Big Hairy Thunderer. One day Ernie is out hunting with the guys when he is struck and killed by lightning. Naturally, the tribe wants to know why the BHT killed Ernie, in order to avoid doing whatever it was he did and meeting the same fate. Someone remembers the time when Ernie stole Ed’s newly sharpened spear because he wanted to hunt but was too lazy to sharpen one of his own. And wasn’t it generally true that Ernie was pretty lazy most of the time? Ah! Now we know how Ernie sinned against the BHT. (Much later, this would be refined and known as the scientific method where the “making something up” becomes a reasoned hypothesis based on close observation.)

What I’m calling a “deep-seated need” to tell and hear stories may have been a key part of the brain’s development. Research in neuroscience suggests that the very act of telling and hearing a story stimulates multiple areas of the brain. Not only that, it seems to affect our social interactions. Admittedly, the research was based on readers of fiction, not verbal storytelling. I think our earliest ancestors must have experienced the same brain stimulation and social development as the modern readers in the experiment.

What does this mean to us writers and readers? According to the article, if you write, “The singer had a pleasing voice,” it’s boring to the reader because the phrase pleasing voice is so generic that your brain ignores it. But if you say, “The singer had a velvet voice,” then the sensory cortex of the reader’s brain activates the same area that identifies textures. The more vivid the writing, the more engaged (stimulated) the reader (brain).

And get this: the research shows that frequent readers of fiction, particularly those who were read to at an early age, have a greater ability to empathize with others. That’s because the readers of good fiction mentally and emotionally put themselves inside the character’s plight. They feel and understand his point of view. Writers do, too, while they are in the act of writing. It’s not possible to write a good emotional scene without feeling what you want your character to feel. The act of telling (writing) and hearing (reading) a story has profound importance in our mental, emotional, and societal development.

So, readers and writers, let’s all keep doing our bit for humankind.

I certainly think story telling is innate to the way people learn. From childhood, our brains are geared to listen to stories and perceive information in the story form. Great stories are what people remember.

Yep. 🙂 It’s pretty exciting – listening to stories stimulates multiple areas of the brain and may have been a key part of our brain’s development.

Love this, Candace. I don’t think any of us writers need validation, but these are wonderful and thought-provoking concepts. It’s easy to believe we do what we do for deep, hardwired reasons. Great post.

I’m awestruck by how fundamental storytelling is to our development. Ever notice how we (the species) spend our time? Listening to stories. Television, movies, books. Even newscasts tell a story. Gossip around the water cooler. It’s fascinating!

Young kids go through a stage when they learn to distinguish the difference between a story and the truth (well, most of us get past that stage). Obviously the storytelling urge is way deep down.

Love the bit about readers and empathy. It figures, doesn’t it?

I was struck by that bit, too, Gordon. It does figure! People who were brought up being read to and who continued to read throughout their lives would naturally have more empathy since the stories stimulate parts of the brain that see, hear, smell, taste, and touch what’s described in them, just as if they were real-world experiences. Stories stimulate parts of the brain that feel fear and joy and all the emotions in between, just as the characters appear to do when vividly drawn. We *want* to feel and see what characters – and real people – feel and see! Why? What draws us? Apparently the development of empathy is a better survival skill in the long run than, say, bashing each other with ever more sophisticated rocks. 🙂

I suspect language may also play a part in memory. Great post.

Good point, Meeka. We have so much to remember besides where the good yams are. So as language developed and became more sophisticated it would follow that memory pathways would do the same.

Hi Candace,

A very nice and thoughtful article.We live vicariously through the sights and sounds of a well told story. Perhaps we are having a personal Zen moment when we see the story come alive in our imagination during the telling and retelling of a good story.

Thank you

Joe

Thanks, Joe. We love stories that are so well written they leave us a bit disoriented when they end and we have to return to reality. We certainly enjoy the telling and retelling (or reading and rereading) those stories we have come to call classics.

Story telling is as old as language itself. No surprise that it boosts brain development – just as music does. 🙂