The publishing industry has changed dramatically over the last forty years. I’ve seen it. My first two books were published by a traditional publisher, a New York house, in the 1980s. That was probably the last time any large publisher took a chance on an unknown. After that, they got much more conservative, much more risk-averse, and pretty much only went with a name that they knew could command sales. Many small presses sprang up into the breach of the 1990s, and then the big explosion — self-publishing — came along after the turn of the century. Now, just about anything goes, and there is a wide range of publishing options for the hopeful author.

The publishing industry has changed dramatically over the last forty years. I’ve seen it. My first two books were published by a traditional publisher, a New York house, in the 1980s. That was probably the last time any large publisher took a chance on an unknown. After that, they got much more conservative, much more risk-averse, and pretty much only went with a name that they knew could command sales. Many small presses sprang up into the breach of the 1990s, and then the big explosion — self-publishing — came along after the turn of the century. Now, just about anything goes, and there is a wide range of publishing options for the hopeful author.

What’s it all mean? Let’s break it down.

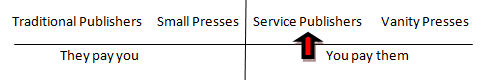

On the left side of this continuum (above), you will see traditional publishers and small presses. Traditional publishers operate on the age-old premise that they will publish your book if they think it will sell. They do not ask you for money, not up front, not ever. They pay you. Decades ago, they might have offered an advance — literally an advance against future earnings of your book — but nowadays that’s rare unless you’re an already successful and well-known name. But even without the advance, as the book sells, they will pay you according to the royalty agreement in your contract. Usually they will take care of editing, formatting, book cover design, and marketing (although that particular effort has diminished greatly over time), all without any cost to you. They are betting they can package your book well enough to earn them back their investment, and then some.

On the left side of this continuum (above), you will see traditional publishers and small presses. Traditional publishers operate on the age-old premise that they will publish your book if they think it will sell. They do not ask you for money, not up front, not ever. They pay you. Decades ago, they might have offered an advance — literally an advance against future earnings of your book — but nowadays that’s rare unless you’re an already successful and well-known name. But even without the advance, as the book sells, they will pay you according to the royalty agreement in your contract. Usually they will take care of editing, formatting, book cover design, and marketing (although that particular effort has diminished greatly over time), all without any cost to you. They are betting they can package your book well enough to earn them back their investment, and then some.

Small presses are really just smaller versions of traditional publishers. They might be a one-man show, or a mom-and-pop operation, but they function in roughly the same way. They think your book is good enough to sell, good enough to earn them (and you) some money. They do not ask you for money ever. They pay you royalties as the book sells.

Now we go to the other side of the continuum. At the far right is vanity publishing. This is an entirely mercenary business model that will publish whatever you want — even gobbledygook — for a price. (I’ve heard someone actually submitted nothing but Lorem Ipsum to a vanity press, and they agreed to publish it.) They will present to you a list of all the work they will perform (editing, formatting, cover design), for the measly sum of only $5,000 or $10,000, because your book deserves the best. Petty cash, right? The problem with this is that (1) they get their money up front so they have absolutely no incentive to sell your book for you and (2) they don’t know if it will sell and they don’t care. They are not in business to sell books. They are in business to take every red cent they can convince you to hand over.

At this point, let’s back up to the left a little, to service publishers. What the heck is that?

Service publishers are akin to vanity publishers in that they will print or publish whatever you have for a price. They will not pass judgment on it and they don’t care if it sells. The difference here is that you know from the get-go that they are selling services, not dreams. Think of a service publisher as a Home Depot or other DIY store. You’re planning a project. You need a hammer? They’ve got one: $14.95. Do you need a new hot water heater? They’ve got that, too, probably a few hundred bucks. Ah, but you need it installed. Okay, sure, they can do that, too, and will quote you a price for time and materials. A service publisher is like that. They will let you pick and choose what you need and give you a price for each item. They will not (usually) con you into anything you don’t need by appealing to your fragile and self-doubting ego. Need editing? You’ll be quoted a price for that, based either on time or on word count, and it could vary depending on whether you need developmental editing, copy editing, or proofreading. Need formatting? You’ll get a fixed price for that, again, possibly based on word count. Need cover design? Same deal. Don’t need those things? Fine, don’t pay for them.

So what’s the catch? There are a couple things to be aware of.

Number one, know what you’re getting. Make sure you understand exactly what the end result of their effort will be. Ask to see samples of other work they’ve done. Get a short list of referrals, if possible, and talk to other clients about their experience, or look up reviews online. Ask about guarantees — if you’re not happy with the work, what then?

Number two, compare prices. There are many service publishers out there; get several quotes if you can. You might see prices for editing anywhere between $300 or $400 up to $2,000 or even $5,000. You might get quotes for formatting that range from $50 to $700. Remember that a high price does not necessarily mean quality work. Both editing and formatting can encompass several components; make sure you know what’s included and what’s not.

If you’re a regular reader here at IU, you’ll know that most of us here do all this stuff ourselves. We may enlist help in the form of beta readers, or we may barter for similar services, but we don’t pay thousands of dollars to anyone. However, we also recognize that not everyone is computer savvy, not everyone is interested in investing the time and energy into learning how to do everything required to publish a book, so if you need help, don’t be afraid to search for it. Just do your research, ask good questions, get quotes, compare, and then ask more questions. It’s your book; it deserves the best. But only you can decide what that is.

Great overview, Melissa.

Thanks!

I find the term “vanity publisher” outdated – it offends me the same way the term “Negro” does. The term “Vanity publishing” was created by traditional publishers to sneer at authors who were so vain (‘vanity’) they would pay someone to publish their books instead of going through the tightly-guarded gates of the traditional publishers. Essentially, vanity presses were then the only alternative to traditional publishing and therefore their only direct competition; hence the need to find a derogative, sneering name for them. “Walden Pond”, like many famous books, was published through a vanity press.

There were two differences at that time between traditional publishers and vanity publishers: 1) Vanity publishing was a service you paid for, which did nothing to sell your books, while traditional publishers did not charge you and often paid a small advance. And 2) Vanity publishers did nothing to sell your books, while traditional publishers vigorously marketed your books, leaving you to simply write the next one.

As we all know, traditional publishers no longer do much to market your book; their marketing budgets are spent sending big-name authors on book signings. These days, either route, you have to market your book yourself if you want any sales. So that “difference” has disappeared, as has the advance in most cases. Now the only real difference is whether an author pays for services such as editing, cover design, formating, printing, and distribution, and keeps the book’s earnings herself, or has it done by a “traditional publisher” who keeps all but a pittance of the earnings himself, AFTER the author has paid in time and money to market the book for him. The term “vanity press’ is rude and outdated; the only distinction nowadays is whether you go through a traditional publisher or self-publish.

There are big and small traditional publishing houses, some specialize in certain types or genres of books, some general houses, all of which which offers different advantages and disadvantages. And there are different ways to self-publish; either you can do everything yourself, or you can pay for certain services. If you pay for all the services in one place, you get what used to be sneeringly called a vanity press type of situation. However, now there are people online who specialize in book covers, or in formatting, or editing; there are print shops; there are people selling their marketing services, etc. You can hire what you don’t want to bother learning to do yourself, and learn what you do want to know and do yourself. But they are all self-publishing. Essentially, you can buy all your shopping needs at one big department store or you can shop around and go to different specialty stores for different services. That;s all. Nothing vain about it.

There are still and always will be predators out there, preying on people’s dreams, as there is in every field of endeavor. You ascribed predators only to some all-in-one self-publishing presses, calling them “Vanity presses”. Sorry, but that is so wrong. The worst (and most common) predators I have run into are traditional publishers who publish an author’s book and then do not pay the promised royalties, but simply pocket the money assuming, usually correctly, that it will be too difficult and expensive for a small author without an agent to take him to court. At least with a “vanity press” you have a product you can sell – the truckload of books you have paid for. Unless you aren’t given the books, in which case you are in the very same position as you are in with a publisher who won’t pay royalties. ANY time you sign a contract or pay for services, you have to beware, check it out in advance. And still you can be cheated. Let’s not compound the crime by accusing the victim of vanity in the first place for paying someone to publish his/her book. There is nothing at all vain with creating a product and paying someone to get it ready for market. It is an act of skill, creativity, persistence, faith and above all courage to do so.

So lets get over this offensive habit of calling ANY type of publishing “Vain”. No other field of work sneers at the entrepreneur. When you use the term “Vanity publishing” you are only buying into the clever marketing strategy of traditional publishers to keep control of their product – which is OUR creativity.

Ms. McLachlan, while I think it’s good that we use language that is appropriate for the day, I must admit I’m a bit taken aback by your comparison of the term “Vanity Publishing” with the term “Negro.” Both are outdated, but one refers to an occupation, the other refers to a person’s entire being. They are not an apples to apples comparison. They’re not even apples and oranges. They might be more akin to apples and bulls. Clearly, you are greatly offended. And while I suspect you have been called a vanity publisher (or user of a vanity publisher) before and are personally offended, have you ever been called a Negro before? As a person who has been called both a user of vanity publishing and a Negro, I can assure you that one term is more offensive than the other. They are not equal in their offensiveness, and to pretend they are trivializes one term.

In my humble opinion, I think you would do better to use comparisons that are equal. Perhaps you are as offended by the term stewardess as you are by the term vanity publisher. Both of those terms are outdated and they both describe business/work functions. If you don’t think stewardess draws the level of outrage as Negro, then you would be correct. And that is a good thing. While it is tempting to compare our outrage to the most offensive thing we can think of, it is not appropriate. It negates the harm of truly offensive things when we compare them to lesser harms that are nowhere in the same league.

Hi RJ,

I did not in any way intend to trivialize the offensiveness of the term “Negro”. I, too, am offended when people are called pejorative names, whether I am part of that culture or not. I said it was offensive in the same way – not necessarily to the same degree – as the term “negro” – because both are used insultingly to belittle others, and that is always offensive. No, I am not a publisher, nor have I ever been accused of vanity publishing my work. I simply find any pejorative word used against other people to be highly offensive – it doesn’t have to be used against me for me to dislike it. Which means I don’t have to be an African-American to find the term “Negro” offensive and insulting. When another human being is deliberately insulted, I am offended.

The term “stewardess” is used not pejoratively, but to describe an occupation. The term “vanity” is not an occupation, it is an insult, clear and simple. It means self-important, puffed-up, lacking in substance or value, self-centered, thinking oneself better than one is. Calling someone those things, in my opinion, is offensive.

Of course, I do not mean to imply that Melissa was deliberately being offensive. I don’t for a moment think that, nor is that what I said. I only said the term “vanity press” is outdated and offensive and should be dropped from use. Arguing that everyone knows what it means is not the point. There are a great many words that we all know what they mean, but we know they are not appropriate to use.

Jane Ann, I hear you. I think you’re right that the term is outdated (your recap of the history surrounding it is true), but I continue to use it because it’s a term that almost everyone understands. I actually think the term has become so commonplace that the original derogatory meaning (being vain enough to write and publish a book) has lost its juice. You’re also right that there are many degrees of methods of publishing, more so than I’ve used here, but a post that tried to go into all those varying degrees would take many, many pages. What I’ve attempted to do here is break it down into its simplest form so aspiring authors can easily sort through–on a top level–what they want and need. As for those varying details, they will have to pick through those themselves and determine what has value for them and what doesn’t. Like any industry, there are zillions of providers and of those some will be ethical and some won’t. Our hope here at IU is that our readers do their research, comparison shop, and choose the right path for them and their book. Thanks for commenting.

There are a great many terms that became commonplace but are nevertheless offensive. If we ourselves won’t drop the words that imply that self-publishing is vain, less valuable, of little substance, how can we expect others to see it in any other light? Words have meaning. Their meanings don’t dissolve by use. You are a writer should respect the meaning of words. I assume you mean what you say. I assume people choose words that accurately reflect their thinking, even if subconsciously. I simply ask all of us to reconsider and stop verbally agreeing with those who would call self-publishing vain.

But Jane Ann, vanity publishers *do* still exist. We did a whole series of posts on them here at IU a couple of years ago. AmericaStar Publishing and Author Solutions are the two big names that readily come to mind. Their M.O. is exactly as Melissa described: they flatter newbie authors into giving up thousands of dollars for books that will never sell. Yes, “vanity publisher” is pejorative — and deservedly so. These companies are out to fleece as many people as they can.

The “service publishers” Melissa is describing in her article are *not* vanity publishers. I would actually call them “service providers” rather than “service publishers.” They are companies that provide certain services to indie authors. Some still overcharge and under-deliver — but not to the same degree as a vanity publisher does. And there are many, many capable and reasonably-priced service providers out there.

Sorry you got hung up on the terminology.

I see what you mean. If they call themselves publishers, and pretend they’ll market the books, they are definitely trying to fool emerging writers.

However, the term “Vanity publishers” did initially cover every non-traditional, paid-for-publishing option. I think rather than trying to redefine the term into only a small segment of paid-for-options we should drop it. We are trying to overcome a stigma, lets not fool ourselves about that. To make sure we eliminate any stigma that old term associates with self-publishing, it would be better to move on.

Rather than blaming the victim, implying the writers’ vanity did them in, perhaps it’s time we simply called them “predatory publishers”. Everyone would know what that means.

While I agree that the switch to the term “predatory publisher’ is more accurate in today’s argot many people still use both interchangeably in the business. In my experience the term ‘vanity publishing’ no longer bears the same connotation as vanity by itself. It no longer implies that the user is ‘vain’. Terms and words evolve and in this case we tend to see users of these scammers as victims, not as vain. In this case it is pejorative, yes, but against the company, not its hapless client.

Excellent post, Melissa. ‘Buyer beware’ has never been more relevant than now, but DIY is not always the answer. Maybe the Indie motto should be DWC: ‘do what you can’. 🙂

Good point, AC. Sadly, there are many people out there who want nothing more than to trick writers out of their money, and there’s no way around them other than doing the research and making sure you get what you pay for. I know not everyone wants to learn how to do the whole smash, but it sure makes you more savvy and less vulnerable to the predators.

I’d quite like it if the term vanity publishing was consigned to the rubbish bin of distant history. It still casts its nasty smears over today’s crop of self-publishing authors because the general population is slow to catch up with the changes in the industry. They don’t know that most of today’s authors are making judicious choices in out-sourcing many of their publishing services to make good books better before they hit the shelves. The term ‘predatory publishers’ is good though because injudicious authors are being fleeced, as you say, by these arseholes offering everything a writer wants to hear then taking thousands of dollars for virtually nothing of value.

I’m glad to offer a range of a la carte publishing services for writers, at an agreed fee, to produce their work to an appropriate standard. If it keeps them away from the predators, I get an extra warm glow of satisfaction. 🙂

Traditional publishers may have narrowed their intake to established authors, but they also now seem to demand a lot more of any unpublished writers. Several years ago I noticed that, among the requirements for a couple of publishing houses, was a comprehensive marketing plan to be composed and submitted by the author along with the manuscript or synopsis. For people like me who are not people persons, marketing is one of the biggest challenges. But, if a publisher wants me to devise a marketing plan on my own – despite no experience in either publishing or marketing – then why should I go with the big-name publisher anyway? They’re also supposed to take X amount of a percentage off the topic of sales receipts, but shouldn’t that percentage be less if I have to do the marketing or any of the other usual services such traditional publishing houses are supposed to offer? And how do I know what that percentage is?

I paid an independent editor to analyze and critique my first completed novel, but that was after careful review of her previous work and a study of the industry overall. I came to trust her and plan to use her editorial services again. I’m also still looking around for an artist to do the artwork for the book.

Writing, like any artistic venture, is a risk. You’re asking people to review your stuff and decide if they like it well enough to buy it and help you earn a decent living. To do well in your particular art form, you have to make certain investments. And all investments – as any financial advisor will tell you – bear some risks. It’s just the nature of the business.

I’m glad, though, that self-publishing has moved beyond the realm of the “loser” designation and has become more and more accepted. As I’ve said before, it just puts the power of the written word back into the hands of the people who should have it: the writers.