I’m lucky in that I’ve got a wonderful pool of friends, fans, writers, and readers with whom I can bounce off the latest ideas for my most recent book. I can either post in secret groups to get a wide-ranging opinion on a book cover idea or a blurb draft, or I can elicit specific feedback from a select few, depending on my need. And why do I do that?

I’m lucky in that I’ve got a wonderful pool of friends, fans, writers, and readers with whom I can bounce off the latest ideas for my most recent book. I can either post in secret groups to get a wide-ranging opinion on a book cover idea or a blurb draft, or I can elicit specific feedback from a select few, depending on my need. And why do I do that?

Because they keep me grounded. They keep me straight. And they tell me when I’m out to sea.

We all know we writers live in our heads. We get a great idea, we set it down, and — from our perspective — it’s a good story. Only problem is, our perspective is not always the one through which a reader reads our story.

I was reminded of this when I asked a focus group to comment on a first draft blurb for my book Stone’s Ghost. It’s about a guy who lives in Lake Havasu, Arizona, and he makes friends with a ghost who haunts the London Bridge. Now, I live in Arizona, and it’s second nature to me to know that the London Bridge is in Lake Havasu. It was dismantled in London, then brought over here, piece by piece, and reassembled over the Colorado River sometime in the early 70s.

However, it quickly became apparent that not everyone was privy to that fact. I had people in my focus group very confused — was the action taking place in Arizona or London?? Okay, my bad. I had to back up several steps and incorporate that brief background into my blurb. I realized that just because Arizona is the center of my universe does not mean it’s the center of the universe for every reader out there. My perspective, my base knowledge, is not necessarily their perspective.

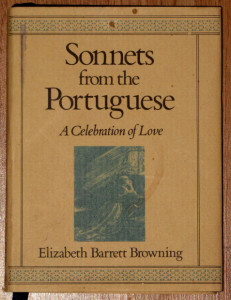

Same for my latest book, Sonnets for Heidi. Now first let me say that I know I was an English geek in school; English was my favorite class every semester, whether it was literature or composition. I read every book ever prescribed by my teachers, memorized every poem, aced the spelling and grammar tests. So when the classic book of poetry, Sonnets from the Portuguese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, figured prominently in my book, my first idea was to feature that book on the cover of my book. Browning’s book is a collection of sonnets she wrote to her husband, Robert Browning, and the subtitle of the book calls it a celebration of love. For those in the geeky world of English literature, it is the epitome of a long and lasting love. The title comes from the fact that Robert’s nickname for his poetic wife was “my little Portuguese.” Most people will recognize the first line of one of the sonnets, even if they don’t know exactly where it comes from.

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

Knowing that the book of poetry personified a lifetime of love, I thought I was being pretty smart to feature it on the cover of my book. But when I offered the first draft cover to my focus group, I got all kinds of weird questions. Was the book set in Portugal? Who was “the Portuguese”? The reference that I thought was clear and obvious was, in fact, neither.

All righty, then. Back to the drawing board. Once again I was reminded that what I know and believe is based on my experiences, my references, and may not be shared by many others — or any others, for that matter. As awkward as it is, it’s a great lesson in humility. It’s a great reminder that just because we know what we’re talking about doesn’t mean our readers do.

The tough part is remembering this because most of the time, our understanding and beliefs are transparent to us. We may be coming from an assumption that is so basic to us, so fundamental, that it’s invisible to us. It just doesn’t seem possible that other people don’t know what we know. But then when we find out that’s not necessarily true, it can be a major sticking point in our efforts to promote our books.

So what’s the takeaway from this? Take your book blurbs and covers out for a test run, and invite your sharpest critics to take a gander at them. Let them do their worst, then regroup and redesign. It’s so much better to find out your primo representations of your book are confusing people before you publish rather than after. At least this way, you get feedback you can use to improve the book. After the fact, well, you just missed a sale that you never even knew about. And no one wants that.

IMHO the main drawback of the Romantic poets is that everything they wrote was so wound up in necessary knowledge, so full of allusions to Classical events and the whole English Public School education they were all so proud of that it made their work impenetrable to the unwashed masses, a group which includes even educated people nowadays. It their day it was clever to be obscure, to make your readers work for every bit of information they got. Fast forward to Ulysses, the ultimate bored game. (See, there I go, alluding. In joke alert!)

Nowadays readers have it too easy. They need everything explained to them, and heaven help the writer who asks them to do a bit of thinking.

That plaint being voiced, it’s the reality of our market, and those of us with a semi-classical education have to learn to adapt. Or get some good friends to help us out

I have heard a couple other authors say they don’t want to “dumb down” their work for their readers. I don’t see it that way. To my way of thinking, I want my readers to ride along the flow of my words without effort, as if the words aren’t even there and the readers are seeing a movie. If they have to stop and get the dictionary to figure out a word I’ve used, then I’ve lost that flow. If they’re confused, they’re not in the story. I don’t consider it explaining everything, but I do consider it setting the stage appropriately. That means giving the reader enough background, enough description, so that the setting seems real. If I’m more concerned with showing off obscure knowledge, then I’m not in the story, either. Guess we’ll have to agree to disagree on that one.

Not at all. I’m not talking about setting. I’m talking about allusion, metaphor, imagery, and all the subtle techniques that make writing richer. I think we can include a reasonable amount of that sort of thing, but the trick is to slip it in with the flow, as you suggest, and not make it crucial to understanding what is going on in the story, because that can stop the reader dead. is that we have to write to our readers if we want to sell to them. I’m agreeing with you on that.

is that we have to write to our readers if we want to sell to them. I’m agreeing with you on that.

And the bottom line, as I mentioned in my bottom line

Thanks for clarifying that for me, Gordon.

But Gordon, back in the day those poets were *popular*. Shakespeare wasn’t writing Serious Theatre in his day; if he were, the Globe Theatre wouldn’t have needed what amounted to a mosh pit.

It’s like kids today who don’t know anything about the Beatles or how influential they were — and still are. There was an incident last year where Kanye West’s fans were talking about this old guy who did a song with Kanye and thought he might have a future in the music business. What was that old guy’s name again? Oh, yeah — Paul McCartney.

Anyway, to your point, Melissa: I highly value my editors, in part because they’re younger than me. There’s a scene in Fissured in which Naomi is watching a couple of shapeshifters fight over her and thinks, “What is this, Twilight?” I had to write it in when Suzu saw a slight resemblance between that scene and the plot of the other series.

There’s a scene in Fissured in which Naomi is watching a couple of shapeshifters fight over her and thinks, “What is this, Twilight?” I had to write it in when Suzu saw a slight resemblance between that scene and the plot of the other series.

Interesting catch of your editor, and a good one, sounds like. Yes, us *ahem* mature writers do well to stay current, or at least employ someone who does. I’m writing a time-travel now, and it’s interesting to see all the pop references that come up in my MC’s brain.

Who was that old guy again? Paul Somebody?

Which leads us back to your title. Knowing what your readers don’t know, so you don’t jar them out of their empathy with the story.

Exactly.

Great post, Melissa and thought provoking too. I personally love coming across obscure references in novels. It’s like finding little gems hidden in plain view, and I always get quite excited when I find one. But I guess those gems really do have to be added extras rather than integral to the plot, or in this case, the marketing material.

Thanks for an important reminder that the story we eventually publish is for the reader, not us.

I think you make an excellent point; those obscure gems are fine, as long as they’re not a linchpin for the story. After all, no one likes to be the one left out of the loop of an inside joke. Your last line is very telling. If we’re writing the story for us, fine, load it up with everything we know about whateveritis. But if we’re writing for our readers, we need to do it without ego and without showing off our intellect. Grandstanding doesn’t leave much room for the reader to connect with us.

I really agree with the “added extra” idea. It works with vocabulary, too. Even younger writers will accept more expressive words, as long as they don’t interfere with the meaning of the sentence, which has to be in words they understand easily.

I believe the standard allowable is three “difficult” words per page for recreational reading.

Wish there was a standard for “references to wonderful old popular musicians that you young twerps really ought to know about.”

Whippersnappers!

Regardless of the cover, it’s a great book inside.

(But you didn’t hear that from me. At least not officially yet.)

Thanks, Al!

How do you tell a story? By communicating. By “eschewing obfuscation.” No need to dumb down, but no need to be pedantic, either. Communicate with your readers if you want to tell them a story.

No need to dumb down, but no need to be pedantic, either. Communicate with your readers if you want to tell them a story.

I think that’s it, Candace; all things in moderation. Thanks.

Two things:

1. If we set a story in, say, the 1970s (When Paul and me were in our thirties!), we need to give our readers a feeling for, and understanding of, what the world was like back then: the way people got their information, listened to music (and what kind of music they were listening to), couldn’t shop on Sundays etc. etc.

2. Our potential readers are subjected to fast paced story telling via TV and the movies. Is there not a role for literature to offer a more relaxed and relaxing – and thoughtful – approach to the entertainment and information we provide.

Two good points, Frank. Especially No. 2. Reading definitely gives people a more thoughtful experience, and if it’s done right, it unfolds naturally, in good time, not served up in whiz-bang 10-minute bytes between commercials. We have the luxury of being able to fully create our story worlds so readers can stroll (or run, with thrillers) through them. Thanks for adding that.