In my reading, I often see questionable usage of a few related punctuation marks. I know (1) that grammar is not every writer’s strong suit and (2) the rules for grammar are more often gray rather than black and white, with lots of room for subjective variation, but a short primer on a few of the more confusing marks might be in order.

In my reading, I often see questionable usage of a few related punctuation marks. I know (1) that grammar is not every writer’s strong suit and (2) the rules for grammar are more often gray rather than black and white, with lots of room for subjective variation, but a short primer on a few of the more confusing marks might be in order.

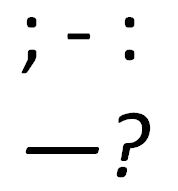

Semi-Colon

Many writers today seem to either hate or distrust the semi-colon, and that could be because they are not clear on the usage (and I won’t even go into the discussion about the spelling, with or without a space and/or dash). Cathy Speight did an IU piece on this persnickety punctuation mark a while back, but I want to talk about it along with some other marks that are sometimes confused, so I’ll recap the semi-colon here as well. Interestingly enough, in the mid-19th century there was an organization of writers in Cincinnati, Ohio called the Semi-Colon Club. Members included Harriet Beecher Stowe and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Salmon P. Chase, among others. I would guess from their choice of name for their group that they were not afraid to use the much-maligned mark.

The semi-colon has two primary uses:

a) Between two closely related but independent clauses, usually complete sentences in and of themselves. The two clauses may also be contradictory.

John chose the yellow kitten; Samantha picked up the calico.

I thought the drizzly rain was uncomfortably chilly; my daughter found it to be invigorating.

b) In a series or list that includes other, internal punctuation that would make the use of commas confusing.

I’m going to have a sandwich of ham, which I got at Trader Joe’s; jalapenos, which came from my own garden; and bell peppers, which were given to me by my neighbor.

Colon

I’ve seen colons and semi-colons used interchangeably, but they are very different and denote different things. The main difference between the two is that the semi-colon is used to link two independent clauses, while a colon is used to introduce an explanation.

The colon has four main uses:

a) Before a list.

Hank packed everything he could think of: shirts, shoes, pants, socks, underwear, books, and his laptop.

b) Before a description.

She loved the look of the vase: its translucent glass caught the light and the yellow color seemed to glow.

c) Before a definition.

He said I was audacious: recklessly bold and extremely original.

d) Before an explanation.

Crossing the Atlantic was hell: the wind howled the entire time and the waves rolled ceaselessly beneath the ship.

Dashes

There are two dashes, the en dash and the em dash. The en dash is a single, short dash (-) while the em dash is a longer dash or two en dashes put together (– or —). The en dash is primarily used to hyphenate words, like space-time. The em dash, however, can be used in much the same way as a colon or a set of parentheses as shown in the following four ways:

a) To denote an abrupt change of thought or feeling.

I was going to say—but, no, I don’t think I will now.

b) To set off a clause.

He was wearing the scarf I knitted for him—the purple one with the green spots—and I realized he was trying to please me.

c) To indicate an interruption, especially in dialog.

“But how do you—”

“Wait! Let me explain.”

d) As the inverse of a colon, i.e. after a list or description.

Black, red and yellow—these colors on insects often denote poisonous species.

There, is that all clear as mud? Just remember that we’re trying to get our ideas across to our readers in as clear a manner as possible, so giving them the right visual clues to follow our line of thought is essential. Happy punctuating!

En dashes are a little longer than hyphens, about as long as an upper case N, but shorter than an em dash (uppercase M length). En dashes are supposed to be used to show range such as “page 45-56” or “1936-1939” meaning “to,” but most people use a hyphen as I just did, not because it’s not an option on an iPhone (as in my case), but because they don’t know it exists. A hyphen, not an en dash, is used to hyphenate words–and two hyphens make an em dash. Microsoft Word will change two hyphens to an em dash if no spaces are used between words (word–word space). One easy way to insert en dashes and em dashes is to access a menu in Word: symbols>special characters. Em dash is first and en dash is second. Hyphens already appear on keyboards.

Good catch, Vincent. You sound like a typesetter!

In Word, click on Insert>Symbol>Special Characters.

I mainly teach college writing, but a long time ago, I used to work for a training company that produced manuals for government employees. I had to learn how to use en dashes.

Thanks for this explanation, Vincent. I can never remember whether it’s the en-dash or the em-dash that’s longer — but I never associated them with N and M until I read your post. 🙂

Vincent, thanks for the clarification. Like most people, I’ve considered the en dash to be the same as a hyphen, and it would appear the en dash is going the way of the dodo, since it’s not on the iPhone. A sure precursor to extinction! And another case of popular usage trumping absolute definition. Thanks for adding to the discussion.

Interesting. It seems I’ve been using an en dash (or hyphen) in place of an em dash.

The en dash is really a secret, mainly known to those involved in printing. Generally, it’s ignored by most writers, but its function is to make number ranges a little easier to read.

Actually, all dashes are available on iPhone and iPad keyboards. The hyphen replaces the “A” key when the number/punctuation keyboard is active. To get en-dash and em-dash characters, touch and hold the hyphen key. The dashes will appear above the hyphen key after a second or two.

Don’t know if they will represent properly here after I submit, but I can type them in Mail and text apps:

Hyphen –

En-dash –

Em-dash —

And on a Mac, the em dash is shift-option-dash (—). For those of you keeping score.

Thanks, I’ll have to try that.

Wow, this is turning into a dash-apedia!

An excellent rundown. My vote goes for “semicolon.” For when we have that discussion. 😉

LOL, see why I didn’t want to get into that??

So, for dummies like me, I see only the hyphen on my keyboard. Where do I find, or how to I create the en dash? I’ve always used them interchangeably.

The fallback position when I forget how to get the long dash is to copy and paste an existing em dash to where I want it. Sometimes Word does the long dash automatically but not always. Clunky but simple solution!

In Word, use Insert>Symbols>Special Characters .

Also, if your keyboard has a numbers pad and you’re using Word, hit CTRL, ALT, and the hyphen character on your numbers pad for the em dash.

Word won’t put in em dashes automatically. It’ll do en dashes for you, sometimes.

Word will put in em dashes automatically IF you do not put a space before or after it. It first types two hyphens, but immediately changes it to an em dash.

I can never remember how to do an en dash so rarely use them.

Thank you. Need I say more?

Your explanation has beautifully eliminated all turbidity of that sedimentary deposit which confuses so many of us. Thank you.

At the same time I feel obliged to point out that with some punctuation there is a marked variance in the conventions employed in different countries who all claim to use the English language. In American English, for example, the comma is used far more freely than in English English where phrases are often allowed to flow into one another. But in Britain we do employ the Oxford comma, which separates the final phrase of a sentence so nicely.

Yvonne: aren’t dashes and hyphens much the same thing? It’s just that to be a dash it needs a space fore and aft. The hyphen splits a word (or joins two words) without a space. Unfortunately many word processing programs extend hyphens or dashes without reference to the writer, and this can cause some confusion.

It was right to label punctuation marks as Pesky. Every time they come up for consideration they provoke limitless discussion which amplifies the confusion as much as it clarifies.

Ian, so I’ve cleared the water or just muddied it more? This is exactly why I gave my disclaimer at the first about the massive amount of gray area in this issue. I know English English uses quotes (single first, double embedded) (before punctuation instead of after) directly opposite of what we do in the US, and I wouldn’t doubt there are other differences I’m not aware of. It makes laying down the law difficult! As long as we’re aware of the many uses, pick a style and stay consistent, that’s about all we can do.

You’re right, Melissa, we do use some things differently, but since it was our language first, and it works perfectly well, why did you try to change it? I think if there is any question of conformity, you ought to conform to our conventions.

I say this very much tongue in cheek for, although I am British born and bred, English is my fourth language and the only one I had to learn in school. I hated English lessons!

Ok, Ian, now you’re drawing a line in the sand. Don’t make us fight the War of Independence all over again! Differences aside, though, I don’t doubt how difficult English would be as a second language. It’s got waaay too many roots sources, hence the many confusing synonyms, homonyms, and redundancies. (But just because your English was first doesn’t make it right!)

Great post, Melissa. Learning a lot about the en dash vs. hyphen.

Probably more than you wanted, right?

When I was working on a nonfiction book, my co-author kept trying to replace my dashes with something else. Somebody must have told him, somewhere along the line, that dashes of any sort weren’t proper for formal written works. Which, as far as I can tell, isn’t true.

Never heard that one, Lynne. But I think some of us hear a “rule” somewhere, sometime, and take it to heart. The truth is, there is a proper place for just about everything; we just have to know the guidelines so we don’t confuse our readers. We want them to flow along on our story odyssey with us, not stop, scratch their heads and say, “Huh?”

Surely it is up to the author to choose whether she or he wants to use dashes. It’s part of the individual style, after all. Perhaps it might be legitimate in academic books for things to be standardised, but the novel is the author’s artistic creating. It’s a cheek for anyone to interfere with tha, although I can understand an editor commenting. At the end’ however, it should be the author’s decision.

By the way, can someone explain the difference between an en dash and an em dash. I’ve never heard of these things before. Are they an American thing? And have I got them on my French keyboard?

It’s not my War of Independence, Melissa. I’m a Scotsman and we’re fighting our own futile one at the moment. I can accept that you might feel your recipe for cheesecake is better than your granny’s because you’ve improved it, but it seems to me that Americans have actually made English more complicated by their changes.

And why do you have to change all our time honoured spellings? Sox instead of socks, plow instead of plough, bow instead of bough, and even honored instead of honoured? There are dozens more examples, as I’m sure you know, but you’ll get my point.

English, proper English that is, shares this unique feature with Gaellic: It’s spelled phonetically. In Garllic the word for red is ‘ruadh’ and we pronounce it as ‘rooh’; the word for life is ‘math’ and we pronounce it ‘vhar’; and the word for whisky is’ uisge’, said as ‘osshka’. It’s simple really.

Incidentally, whiskey, that brown spiritous stuff they make in the US, is known as ‘paotoin’, said as’ potchn’.

But don’t look at the punctuation, that’s a nightmare.

Ian, I take back everything I said about English being difficult to learn as a second language. Remind me that I never want to try to learn Gaelic. (My spell-checker insists it’s only got one L.) I think you guys just stick extra letters in there to confuse us poor Muricans, just like the French do. Why use 10 letters when you can get by with 4 or 5? Your spellings may be time-honored, but ours are practical. Sometimes. BTW, I love a Scottish accent and tried to read your comment with one, but it breaks down when I get to that unpronounceable Gaelic.

I speak English as well. On occasions I even speak Murican! Even worse, Mexican Murican!

But I still don’t understand the difference between en dashes and em dashes, dash it!

Check Vincent’s comment at the top; he does a good round-up of the dashes.

There is a variation in the format of em dashes. Most style books indicate no spaces before and after em dashes: Drive the truck slowly—very slowly.

However, the U.S. military and some corporations use spaces before and after the em dash: Drive the truck slowly — very slowly.

Most writers follow the no-spaces format.