Guest Post

Guest Post

by Shaun J. McLaughlin

One of the challenges facing authors of historical fiction is to be true to the era in which you set your story. You must do more than engage and entertain your readers: you must not misinform.

If your story is set in the eighteenth century, your protagonist should not be wearing a wristwatch. That’s obvious. What is not always obvious are the verbs and nouns we choose for narration and conversation. Make sure those words were part of the common vernacular in your story’s era.

Sound difficult? Well, thanks to the benevolent geeks at Google, there is an app for that. It’s called Google Books Ngram Viewer. In 2009 and 2012, Google created databases of words in all its digitized books, and organized those words by the year of publication.

You simply enter the case-sensitive word or phrase to search for, set a year-range, select the corpus and click the search button. Ngram Viewer returns a graph of the usage as a percentage of words in the selected corpus.

Here are a few examples of how Ngram Viewer improved the historical accuracy of my novels.

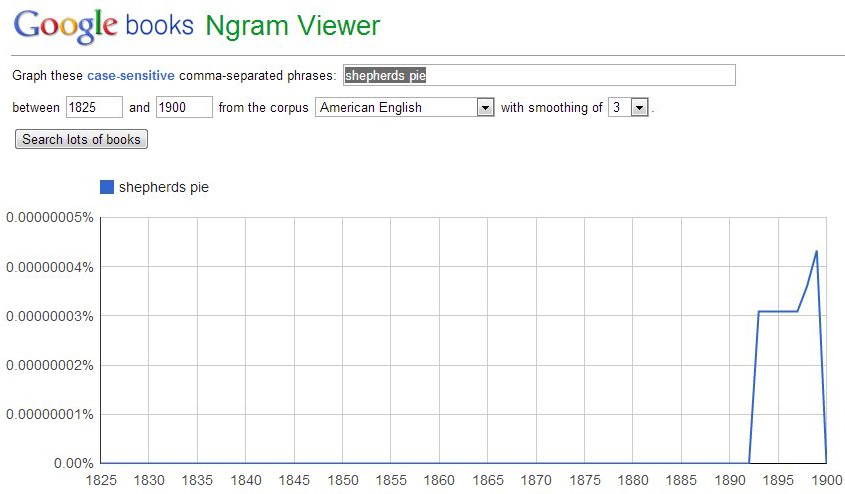

In my 2012 novel Counter Currents, set in 1838 North America, I wanted to serve the protagonist a lunch of shepherd’s pie. So, I entered the food name, set the time span from 1825 to 1900, and picked the American English corpus. (I used a 75-year range to learn when the term came into use if outside of my story’s era.)

The result shows that shepherd’s pie did not appear in books until about 55 years later, and even then, rarely. (Before then, the dish went by the name cottage pie. How I know that is a different story.) This technique is handy for verifying food, clothing, people’s names, and manufactured items.

Ngram Viewer can also help with regional dialect. In my current sequel to Counter Currents, set in 1845-1855 Australia, I want to include some Aussie slang. I entered “billabong” (a term for a type of creek) in Ngram Viewer. No luck. That word doesn’t appear until after 1880.

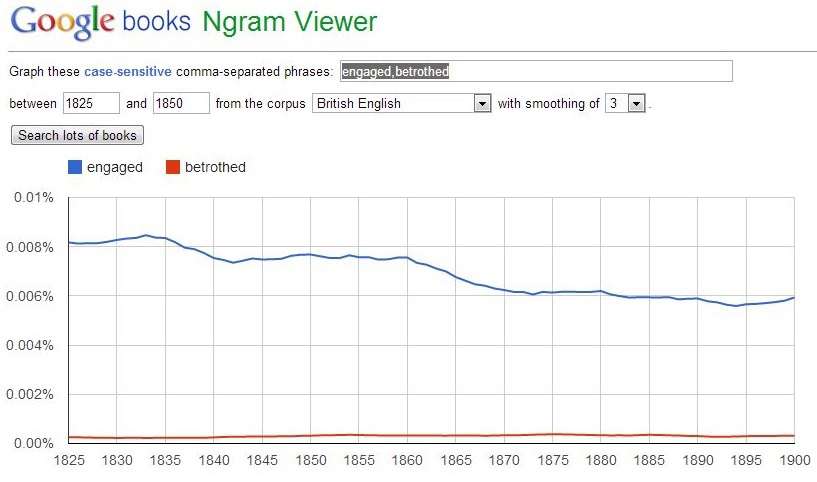

The Ngram Viewer also lets you use the best word if several are available. In my sequel, my protagonist agrees to get married. Which is the best word: “engaged” or “betrothed”?

To graph more than one search term, separate each with a comma.

This graph shows that both words are valid but books used “engaged” more often in that era. I used the British English corpus as the most likely to reflect nineteenth century Australian English.

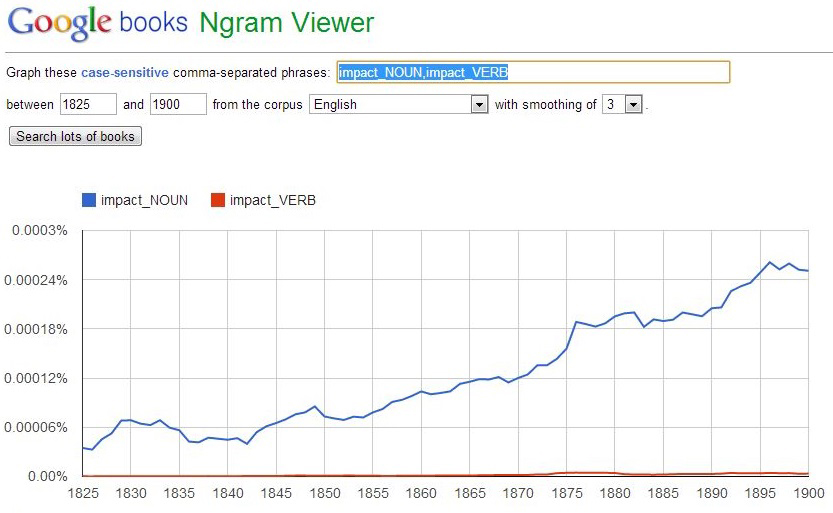

In English, you can use just about any noun as a verb. Before you do, make sure the spoken language in your historical era used that verb form?

Ngram Viewer can graph the same word used as different parts of speech. You just add one of the many available tags to your search terms. (Click the About Ngram Viewer link at the bottom of the Ngram page for details on the many tags and other advanced features.)

In this example, I add the tags _NOUN and _VERB to the word “impact.”

This graph shows that books did not include “impact” as a verb until the 1870s, and very rarely compared to the noun form.

The corpus list provides several choices for English books—all English books, British English for books printed in the UK, American English for books published in the US, and just English fiction books—plus seven other languages. (Use the 2012 versions without the dates, not the 2009 versions: the OCR technology used in 2012 created fewer spelling errors. )

Pick the English corpus that suits your geographical location to help refine your word selection. For example, Ngram Viewer shows that American books used the word “boss” as a noun sporadically in the eighteenth century, but English books used it throughout that period. (I entered “boss_NOUN” in two separate searches using a different corpus.)

Am I suggesting that you run every verb and noun through Ngram Viewer? Of course not. If a word sounds like slang, or your inner doubts nag you (trust your intuition) or you are faced with several synonyms, use it. It takes just seconds.

Shaun J. McLaughlin has authored books on history and historical fiction, using both a traditional publisher and self-publishing. A researcher, journalist and technical writer for over thirty years, he lives on a hobby farm in Eastern Ontario, where he focuses on fiction and nonfiction writing projects. For more information, see Raiders and Rebels Press. or visit Shaun’s Author Central page.

Thank you. I wish I had known about this when I began my trilogy. While it is not set in an actual society, it is an ‘old world’ place. I have done my best to give my language, particularly dialogue, that flavour. There were times when I wanted to check a word and could not find it’s history.

Yvonne,

Dictionary.com usually has the history of any word you look up near the bottom of the page. I quite often use it.

Thank you. I have tried it on occasion, but some words could not be found there.

Fantastic resource, Shaun! Will bookmark and send links to my historical and time-travel writer friends.

What a great resource. Thanks, Shaun!

Thank you, Shaun! I can see this coming in handy.

Excellent tool…thanks!

Before the Internet, we used the old standby Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary which gives the year it came into existence and very handy when writing historical fiction. I still have my 1987 publication and kept it close because I didn’t know about this new way and didn’t think to use the Internet to look these days. Great post, thank you.

Before the Internet, I used to spend hours in a library and carried home piles of photocopies. I can do that all from home, save time and gasoline, and stay paperless. We authors are blessed with conveniences.

Isn’t the internet just bloody fantastic!!! There’s really no excuse for writers to dally with research taking years to complete a book when it’s all there at our fingertips now. (Damn, must get off my backside and publish the WIP – enough is enough!)

This is an excellent resource and I’ll rush to tell all my writing groups immediately.

Thank you, Shaun, this is definitely a resource to bookmark. I have always, definitely gone out of my way not to use current vernacular when writing historical fiction; however, I usually make do with writing full and proper English (no isn’t or wasn’t et cetera) and with the odd vintage term thrown in for effect. Because, although I like the general facts and feel to be authentic, I am writing for todays audience and I don’t want to bog the story down and alienate those readers who would never dream of (as I actually do) having a dictionary, thesaurus and other reading aids to hand.

Excellent, article, Shaun.

Contractions do appear in older writing. To search them in Ngram Viewer, you must enter part of the word without the apostrophe. So to search for isn’t, you use isn.

That’s helpful. Thanks

Now if that ain’t slicker than snail snot, I don’t know what is! Great article, and I’ll check that out since I’m writing an historical fiction screenplay at the moment. I have book resources, but sometimes I have to create my own dialog, so this will be a big help.

I am glad everyone found my article useful and “slicker than snail snot.” IU is my favorite source for writing tutorials and tips, and I am happy to contribute.

I loved that phrase, too. It was the biggest laugh of my day.