Foreword, preface, prologue. We’ve all seen one or the other of these at the front of a book, and many people think they are the same thing. They’re certainly very similar, but there are definite distinctions between them. Do you know what they are?

Foreword, preface, prologue. We’ve all seen one or the other of these at the front of a book, and many people think they are the same thing. They’re certainly very similar, but there are definite distinctions between them. Do you know what they are?

A foreword is a short introductory statement, especially when written by someone other than the author. It’s not unusual to see the writer of the foreword lauding the author of the main work, or telling a bit about how the work came about or how it came to his/her attention. Note that the definition describes it as a short introductory statement. Usually a foreword is a few paragraphs and less than a page.

The opposite of a foreword is an afterword: a concluding section or commentary or a closing statement.

A preface, conversely, is a preliminary statement by the book’s author or editor, usually setting down its purpose and scope, expressing acknowledgement of assistance from others, etc. Very often we will see an acknowledgment page used for this purpose instead.

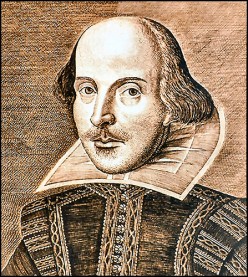

A prologue is described as a preliminary discourse, an introductory part of a poem, novel or play. It can be an introductory speech calling attention to the theme of a play, as Shakespeare often did. In Romeo and Juliet, the prologue is as follows:

Two households, both alike in dignity,

In fair Verona, where we lay our scene,

From ancient grudge break to new mutiny,

Where civil blood makes civil hands unclean.

From forth the fatal loins of these two foes

A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life;

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark’d love,

And the continuance of their parents’ rage,

Which, but their children’s end, nought could remove,

Is now the two hours’ traffic of our stage;

The which if you with patient ears attend,

What here shall miss, our toil shall strive to mend.

These days, a prologue like this would likely be regarded as a spoiler, but a subtler version could be used to draw the reader’s attention to a theme or a thread that might otherwise be overlooked amid the action of the story. The prologue will usually hint at what is to follow, and give the reader a sense of the flavor of the story.

The opposite of the prologue is an epilogue: a concluding part of a literary work like a novel, or a speech after the conclusion of a play. This is very often used as a wrap-up, tying up the loose ends or letting the reader know what happened to the characters after the climax of the story. It may pull the entire story together, capturing the theme in a final, brief resolution.

Where a foreword or a preface is not integral to the story, the prologue is. A word of caution here, however. While the prologue may be used to set up the story, beware of using it as an info dump: filling it with names, dates, and relationships that, at this point, mean little to the reader.

Here’s a sample of how NOT to write a prologue:

Blonde and petite Christina Butterfield Warren, a clairvoyant who shares her prophetic powers with her twin brother, Anderson, has been shielded by her parents, George and Regina Warren, for the first sixteen years of her life. Now, however, at their untimely deaths, Christina finds herself at the mercy of her cruel uncle, the Duke of Warrenham. Forced to leave the only home she’s ever known in Nodding Hill, she arrives at Warren Hall in Piddlington where her older cousin Frobisher seems to offer a sympathetic ear. But can she trust anyone in Warren Hall? And does the appearance of the specter of her granny Hawthorne mean madness or truth?

By contrast, the prologue to the original Star Wars gave the viewers just enough information to understand the action that’s taking place and introduced them to one character only. All the other characters were introduced during the unfolding of the story, allowing the viewers to get to know them one by one.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away….

It is a period of civil war. Rebel spaceships, striking from a hidden base, have won their first victory against the evil Galactic Empire. During the battle, Rebel spies managed to steal secret plans to the Empire’s ultimate weapon, the Death Star, an armored space station with enough power to destroy an entire planet.

Pursued by the Empire’s sinister agents, Princess Leia races home aboard her starship, custodian of the stolen plans that can save her people and restore freedom to the galaxy…

Prologues, used correctly, can set up a sense of anticipation in the reader, drawing them immediately into the story, making them want more. A prologue that provides too much information too soon, however, can often produce no more than a glazed look in the reader’s eyes and a temptation to move on to more subtle, but infinitely more interesting, stories.

Choose wisely.

Melissa: Great post. Much of what you write fits nicely into a paperback/hardback, but I don’t tolerate it well in an ebook. I’ve discovered many ebook prologues read similar to an outline. They often tell too much–as if the author is writing a book report for 10th grade. One of the key elements you mention is to not introduce more than the main character–that serves in a blurb as well.

Jackie Weger

Good point, Jackie; we need to tell just enough to make it interesting, but not so much that we overwhelm the reader with details that don’t make sense yet. Thanks for adding that.

Excellent post. You spelled it out so clearly. I used the epilogue from my first book in the trilogy as the prologue in the second. My reasoning was to situate readers who had not read the first. I debated endlessly with myself about including it and even now I’m nor sure it was the right decision.

That actually sounds like a good fit (altho that’s saying it without reading it myself). It seems to me it’s very hard in a series to bring a new reader up to speed if they’re starting with a later book.

Really helpful, Melissa. I hadn’t given much thought to the differences earlier, but you’ve spelled them out clearly. Thanks.

Interestingly enough, with my research, I discovered I’ve misused several of these things! Never too old to learn, tho!

The prologue is just one more tool to get the reader to read the book. Therefore, like the title and the blurb and the table of contents, it has to attract attention, raise questions, reach out and grab the reader until he or she just has to read that book.

Like a good TV commercial, the prologue should be a story in itself, a story which raises a question, the answer to which is the whole novel to come.

For example, a standard prologue for a fantasy is the birth of a child. The task of the author is to make that child so special that the reader just has to know what his or her life will be like.

So when I see people expressing the opinion, “I never read prologues, I hate them,” I blame the bad writers mentioned above, who use their prologue as an info dump. Face it, folks, at that stage of the story, nobody cares about details. Your job is to make them care.

What the prologue also should do is introduce the theme of the story. Once again, if the theme is something that the reader really cares about, the prologue is there to entice the reader to read more. If the theme is not something the reader cares about, then it’s probably a good place for them to find out 🙁

The epilogue, of course, is a cheat. The reader thinks it’s there to give some idea of what happened to the characters later. The author knows it’s the hook for the sequel 🙂

Good points, Gordon; definitely one time when less is more. The prologue should tease, not flood the reader. As for the epilogue, I’ll defer to you, since I’ve never written a sequel!

One of my novels has an overture and underture

Why am I not surprised?

Great info. Although not a fan of writing any of those, it’s good to know should I ever be tempted.

Some stories lend themselves to these add-ons, while others don’t. I’m sure if you get kidnapped by one that does, it’ll let you know!

I think a number of authors ought to just re-title their prologue “Chapter 1” and be done with it. 😉

I’ve used epilogues at the end of both of my series. In each case, some time has passed since the main action of the series has ended, and the epilogue gives the reader (I hope!) some perspective on the events. It also allows me to tie up all the loose ends.

Great post, Melissa. 🙂

Thanks, Lynne. I like epilogues. As with those you see at the end of movies (like American Graffiti), it lets you know what happened to the characters. Always interesting to see how people end up!