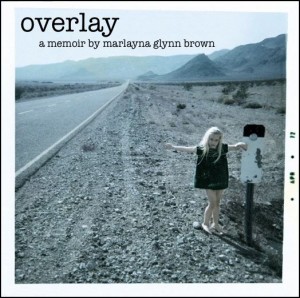

Today we have a sneak peek from the memoir by Marlayna Glynn Brown: Overlay – A Tale of One Girl’s Life in 1970s Las Vegas.

Today we have a sneak peek from the memoir by Marlayna Glynn Brown: Overlay – A Tale of One Girl’s Life in 1970s Las Vegas.

Fans of The Glass Castle will appreciate this extraordinary tale of the author’s turbulent yet triumphant childhood in 1970s Las Vegas.

Born into an ongoing cycle of familial alcoholism, the author develops a powerful sense of self-preservation contrasted by the people entrusted with her care. She explores the personalities of the bizarre characters who populate her life as she moves from home to parent to friends’ families and ultimately to homelessness as a young teen.

From her remarkable resources emerges an inner strength that will captivate readers, remaining in their consciousness long after the last page has been turned.

Overlay – A Tale of One Girl’s Life in 1970s Las Vegas is available from Amazon.

And now, an excerpt from Overlay…

The next day is Christmas, and my mother works while my father stays home. He smokes while I open my gifts. I don’t much like being around him when he’s drinking, which is all the time he’s home, because his reactions become increasingly slow, making it nearly impossible to hold a conversation with him. Whenever I ask a question he turns his head, gazing at me through the blue haze of cigarette smoke.

“What… Penut?”

“I asked why you call me Penut.”

He pauses for a long time as if the answer to my question could only be found deep within. I think he isn’t going to answer at all when he finally says, “When you were born, you looked like a shriveled little peanut….”

“Then why do you call me Runt?”

Moments pass. “A runt is the smallest animal in the litter. You’re the smallest so that makes you the runt.”

“Why don’t you have more kids then? I wouldn’t be the runt anymore.”

My father exhales a lungful of smoke and doesn’t say anything for a long time. “More kids?” He laughs, a strange sort of laugh-chuckle-cough. “You weren’t even supposed to be here….”

To this, I have no response. How in the world could you be here when you weren’t supposed to be here? I leave the living room and its Christmas tree smell and run down the dark hallway into my parent’s bedroom. Tucked against one edge of the dresser mirror are two faded sepia photographs of two dark-haired children that have been there for as long as I can remember. The edges not tucked under the mirror curl up sideways as if reaching for freedom from the mirror’s grasp. The boy is my brother and the girl is my sister and they live with their father in California.

I take the pictures down and examine them carefully as I sometimes do. These two children don’t look anything like me. My brother has dark hair and big ears that stick out from the side of his head like two happy beacons. I stare back at his joyful, crooked smile and imagine it is just for me. I switch my eyes from his smile to look at my sister’s elfin face. Her short black hair falls unevenly above her dark, troubled eyes. So envious of the similarity in their dark features that bonds them together, makes them a team, marks them as family, I look unhappily into the mirror at my own solitary blonde hair. I hold their pictures in my hands, side by side, gazing at their dark, secret looks.

Perhaps they aren’t supposed to be here either. Perhaps that’s why they aren’t here with us today. What does this mean for me?

What are the odds that I will remain here?